Clue

I have a problem. Nobody will play Clue with me. Yes, I’m talking about the Hasbro board game that you probably haven’t played in 15 years. It’s one of my childhood favorites, but none of my friends will touch it with a ten foot pole.

It’s not their fault, though. You see, while I was growing up we would play Clue as a family. It was usually just me, my sister and my mom. When we would talk Dad into playing, he would always beat us by solving the puzzle in the first few rounds, long before the rest of us could get close. It was that experience, knowing that I was playing the game wrong, that led me to a better way (read: more annoying) way of playing.

Before I knew it, I was solving the puzzle on the first turn, often before some people had even taken a turn. My friends took the obvious recourse and now we play games like Settlers of Catan, or Republic of Rome, or Dixit. Alas, all my strategy was for naught.

So why talk about it now? Why bring it up? It’s indicative of a greater idea, as all good life metaphors are.

The idea that you can change how you play a game, or do some task, and it can break all sense of competition. Suddenly you are no longer on an even playing field. You win, not just occasionally, but always!

The metaphor is all around us. Take the NSA as a great example in the media right now. They changed the game by doing what few suspected was possible or plausible. Their reach provided them a level of power that cannot be matched across the globe. But what happened when people discovered their secret? Nobody wants to play their game anymore.

Maybe it’s a stretch, but I see the pattern a lot. Sometimes it’s in a field where advantage is positive, like a business offering something others can’t touch. Other times it’s creepy government dudes watching you on your webcam.

So what about me and my love of Clue? Could I go back to playing it the old fashioned way? I suppose it’s possible, but then the temptation to use more advanced strategies would be powerful, and there would be nothing there to stop me. Would my friends even trust that I’d play that way? Probably not. They know me too well.

Instead, I have to accept that I’ll probably rarely have the opportunity to play Clue again. If I want enjoyment from it then I’ll have to find another approach. To that end, I’m going to share a few of my Clue techniques so anyone who reads this can enjoy ruining a childhood game on their own.

Warning: If you try the following techniques you will probably be ridiculed and shunned by all Clue-lovers around you.

Lesson 1: The score sheet is useless.

The little sheet that comes with the game of Clue (seen above) is severely lacking. In the Master Edition game, at least, they give you some blank space to the side for “notes”. That’s what you really need: some blank paper. Any old blank paper will do. You can keep your score sheet as well and use it to tick off some discoveries, just not in the way the game makers expected.

Lesson 2: Note everything

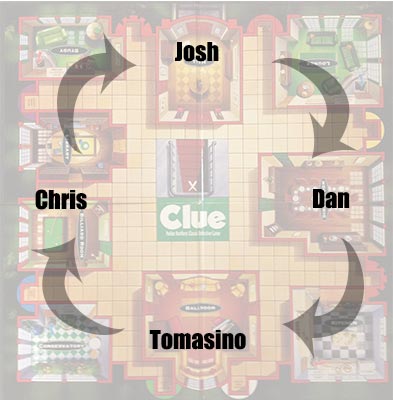

The hardest thing to grasp is that everything you hear around the table is helpful, not just the questions you ask. If the player to your left makes an accusation and that accusation is answered by another player before you, you’ve gained incredible insights into both players hands. Lets look at an illustration:

In this game, to my left is Chris, across from me is Josh, and to my right is Dan. In my notes I refer to us as T, C, J, and D to save space. In fact, I’m such a fan of saving space (I hate writing by hand) that I use letters to represent the people and objects in Clue as well: M - Col. Mustard, P - Prof. Plum, K - Mrs. Peacock, and so on. I use two-letter abbreviations for the weapons: Kn - Knife, Ca - Candlestick, etc. And finally, I just number the rooms cause there’s so many of them: 1 - Hall, 2 - Lounge.

This codifying is completely unnecessary to the strategy, but it makes for concise notes, and it’s hard to read when someone sneaks a peek at your sheet. If you’re a fast writer, by all means feel free to write out the full names of things. I won’t stop you.

Using my codes, I make notes of everyones accusations in a vertical column in my notes, like this:

C ( S, Kn, 1 )

In this example, Chris made an accusation that Ms. Scarlet used the Knife in the Hall.

When someone responds to the accusation, I note who they are and any possible answers they gave:

C ( S, Kn, 1 ) -> D ( S, -, 1)

In this example, Dan is the one who responded to the accusation. He possibly showed Chris either Ms. Scarlet, or the Hall. I know he didn’t show Chris the Knife, because I have it!

So what did this teach me? Well, now I know that Dan has one of two items, but I also know that Josh, who came between them, definitely does NOT have either Ms. Scarlet or the Hall. I note this as well to finish my line:

C ( S, Kn, 1 ) -> D ( S, -, 1 ) = J ( !S, -, !1 )

My notation is sort of programming based, but really I’m just trying to show negatives with “!” symbols. Again, everything is concise.

Lesson 3: Logic

Now that I have a broad array of data, it’s important that I review it after each accusation, not just on my own turn. Knowing that Dan has either or both of Ms. Scarlet and the Hall, I can try to see if either of those cards pops up as being held by a different player. If so, I can cross them off as being Dan’s. Through a process of elimination I you can find an amazing amount of information without it being your turn at all. This is also where I bring the score sheet into play. I like to use all the columns, one for each player, and the final column for the solution. In each player’s column I mark down a “*” if I know they have that card, and I mark down a “-” if I know they don’t have it. In the final column, I mark off a “-” if I know someone has the card. The final column will quickly sort itself down to just a couple remaining options.

Lesson 4: Trickery

When making an accusation yourself, it’s almost always better to guess one or two items that you already have, especially when trying to narrow down a category to a specific person, place or thing. You can also use what you know about people to tailor your accusation. If I know Dan has the Hall, but not Ms. Scarlet, I can guess both to see if Chris is secretly holding the Scarlet card. If not, I just solved a third of the puzzle, but nobody else knows this because Dan will show me the Hall when the question gets to him. In short, use what you know in creative ways to stay unpredictable.

Lesson 5: Always show the same card

This final bit is a small thing, but it can have big implications. If you’ve been forced to reveal a card, say, the Knife, then go out of your way to show that same card again and again, especially to the same person. If you are holding two cards from someones guess, but always show the same one, that’s a bit of misinformation that is easy for others to overlook. It makes things a bit harder on the other players

Well, that’s it. Try out that the techniques and you’ll beat the pants off your friends and ruin a decent kids game. Of course, you can use the strategies and let the game linger a bit if you want, too. Maybe people won’t notice and you can become the world’s first Clue shark. How lame would that be?